With a viable COVID-19 vaccine drawing closer to completion, public health officials across the country are gearing up for what will be the most monumental vaccination effort in U.S. history; an undertaking that must distribute hundreds of millions of doses, prioritize who’s first in line and ensure that people who get the initial shot return for the necessary second booster.

Oregon is among many States to have already drafted a plan of attack, from identifying high-risk groups, dividing vaccination efforts into "phases", and working closely with the CDC to further implement this plan into a smooth-running operation.

A drive-thru flu clinic in Carlton, Minnesota served as a test run for the COVID-19 vaccines that county health officials still know little about. Image Via / Jared Hovi / Carlton County GIS via The Associated Press

Health-care workers are our first line of defense, and would likely be prioritized as first to receive a vaccine.

“If you get 10,000 doses, what are you going to do, versus 100,000 doses?” said Dr. Frank Welch, director of Louisiana’s immunization program.

State and local officials are also planning for the likelihood that the first shipments will not be enough to cover everyone in high-priori%ty groups.

Because of the likely need for two doses given three or four weeks apart, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is considering ways of helping Americans remember the second shot, including issuing cards that people would get with their first shot, akin to the polio immunization cards many older Americans remember carrying.

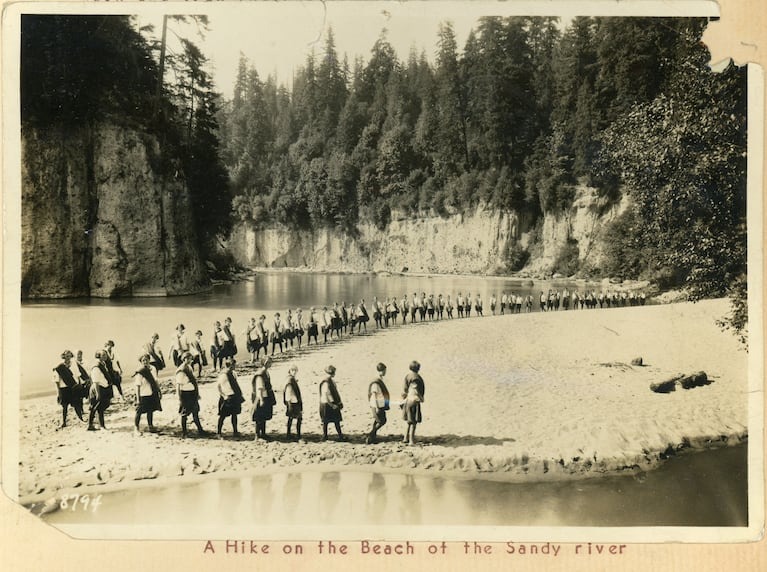

Oregonians in 1954, receiving the first shipment of Jonas Salk's Polio vaccine. Image via / The Oregonian / Archives

Reminders by text message and calls from healthcare workers may also be used to further jog the memory of recipients when the time for a secon shot draws near.

Still, “there will still be some that slip through the cracks,” said Ann Lewis, CEO of CareSouth Carolina, which runs the health centers.

Distributing doses is another concern. The 90% effective Pfizer vaccine, which could be the first to get the green light, comes in shipments of nearly 1,000 doses.

“A minimum of 1,000 doses makes it very difficult to get smaller facilities vaccinated,” said Rich Lakin, director of Utah’s immunization program.

Shipments might go to a hospital that is easily accessible to health care workers from multiple sites, Lakin said. In rural ares like Eastern Oregon counties, it may be necessary for people to drive long distances for access to a vaccine. Mobile clinics may be the answer, with staff on hand to drive units to communities in need.

That Oregon Life will continue to update as new information becomes clear.