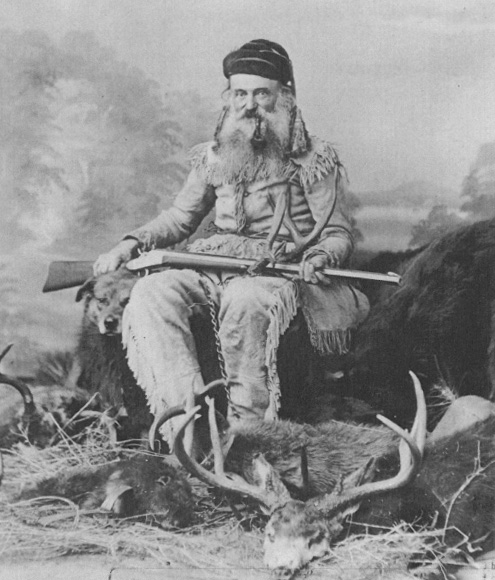

In the annals of the American West, the tales of mountain men and trailblazers endure as gritty testaments to humanity's fortitude. Among the pantheon of pioneers, Steven Meek, a larger-than-life figure, holds a prominent place. His name, forever engraved in history, gives title to the unfortunate Oregon expedition of 1845 - the Meek Cutoff. As elusive as the horizon, the tale of this journey intertwines tragedy and triumph, casting an enduring shadow on the canvas of American pioneering history.

The Legend of Steven Meek

Steven Meek was a mountain man. A hard-as-nails figure in buckskins who traversed the rugged North American landscape long before white civilization set in. Born in 1807, he spent most of his legendary life as a fur trapper, rubbing elbows with the historical figures who shaped Oregon and the West.

Steven's younger brother, Joe Meek, was somewhat legendary himself; he served on Oregon's first Provisional Legislature and became well-known in politics of the day. But while Joe was content to work his land in what's now Hillsboro, Oregon, Steven retained his wild streak. He became a well-known guide in the Oregon Territory, having good knowledge of the land and where crucial, life-sustaining water lay.

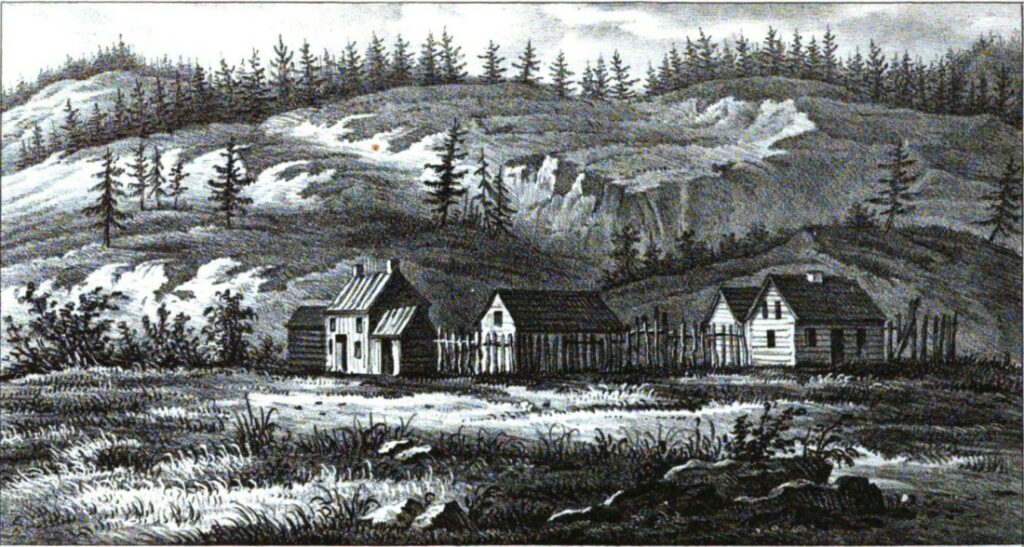

Southeastern Oregon, An Inhospitable Place for Early Settlers

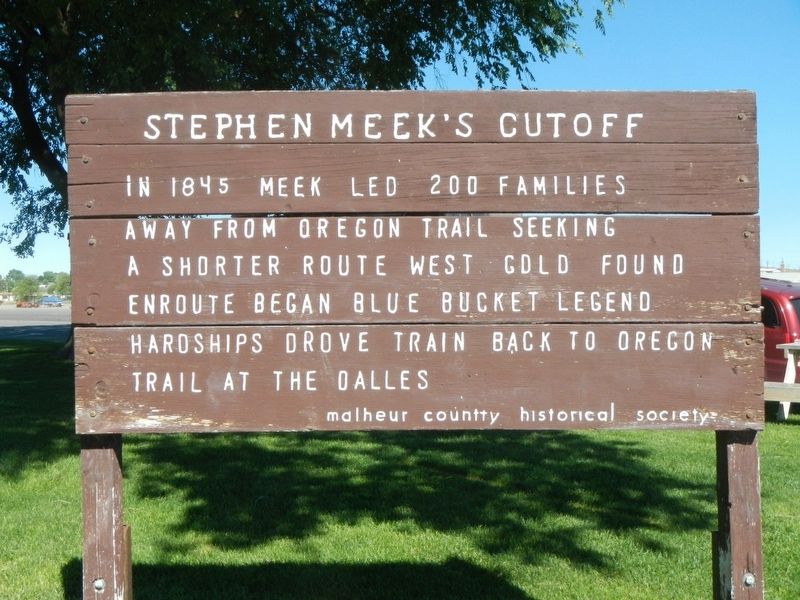

In the summer of 1845, nearly a thousand pioneers packed their lives into canvas-covered wagons and set their sights westward, drawn by the siren call of Manifest Destiny. The allure of verdant valleys and golden opportunities in western Oregon beckoned them onward. Steven Meek promised to shepherd them through the wilderness. His proposition was simple: A shortcut through Oregon's unforgiving terrain that would trim weeks off their journey, avoiding a rugged climb over the Blue Mountains (between today's La Grande and Pendleton). The eager settlers entrusted their destinies to this grizzled pathfinder, unaware of the hardship that awaited them.

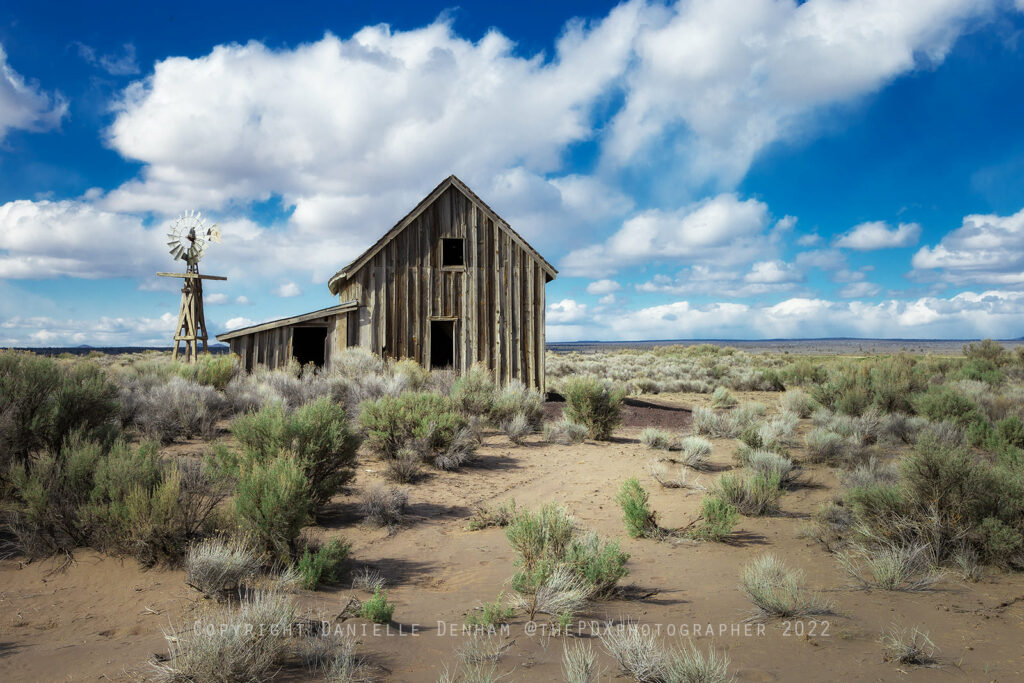

Having explored the paved highways and graveled back roads of what are now Malheur, Harney, and Crook Counties from the comfort and safety of an air-conditioned vehicle, I cannot fathom the sheer grit it would take to make that journey on foot. That section of Oregon's high desert is unforgiving. Today's modern landscape is marked by verdant, irrigated ranch land, but in 1845 it was virtually unexplored.

Meek knew there was water aplenty in the arid desert. 10 years earlier on a trapping excursion he'd seen it with his own eyes; vast alkaline lakes and flowing rivers to sustain people and livestock. Over 1,000 folks believed him, enough to turn their 200 wagons from the well-traveled northward route and follow Meek southwest into the desert.

"Dear Mother, brothers, and sisters,

After travelling [sic] six months we arrived at Lynnton on the Willamette

November the 1st .... We got along finely until .... along came a man by the name of Meiks [sic], who said he could take us on a new route across the Cascade Mountains to the Willamette river in 20 days, so a large company of a hundred and fifty or two

hundred wagons left the old road to follow the new road and traveled for two months over sand, rocks, hills and anything else but good roads...."

--Mariah King, 1845

Evil Hour: An Omen of What Was to Come

At Farewell Bend on the Snake River bordering Oregon and Idaho, Meek's party broke away from the rest of the train. They were to trek along the Malheur River for a bit, then follow the river's north fork down into the Harney Basin.

20 years prior, Peter Skene Ogden, a Hudson's Bay Company trader, referred to this river in his journal as "Riviere au Malheur" which translates as "unfortunate river." Malheur is a french word, loosely meaning "calamity" or "misfortune", and in literal translation, "evil hour".

On the wagon train, tensions rose like the sun each morning, as tales of hostile natives and treacherous landscapes swept through the camp like wildfire. Yet, despite their growing fear and unease, the pioneers pushed forward, guided by the unwavering confidence of their intrepid guide, Steven Meek. The landscape changed from the familiar comfort of meandering river valleys into an ocean of sagebrush and rock.

With each passing day, the promised shortcut seemed more mirage than reality. Water was as scarce as the pioneers' dwindling faith in Meek. It was true that water was plentiful on his earlier excursion through these parts, but he had no way of knowing that 1845 was a drought year. The lakes had dried up, and once flowing creeks were mere trickles.

Related: Play The Oregon Trail Game Online – An American Classic

Raging Fever and Tensions

As desperation mounted, food supplies dwindled. The pioneers had stocked their wagons with provisions for a journey they expected to be weeks shorter. Starvation began to take its toll, joining exposure, dehydration, and illness as grim reapers within the wagon train.

"....Two thirds of the immegrants [sic] ran out of provisions and had to live on

poor beef ... But worse than all this, sickness and death attended us the rest of

the way ... after we took the new route a slow lingering fever prevailed. Out of

Chambers, L. Norton's, John [King]'s and our family, none escaped [the fever]

except Solomon and myself. But listen to the deaths. Sally Chambers, John King

and his wife, their little daughter Electra and their babe, a son 9 months old,

and Dulaney C. Norton's sister are gone. Mr. A[rnold] Fuller lost his wife and

daughter Tabitha. Eight of our two families have gone to their long homes ....

Those that went the old road got through six weeks before us, with no

sickness at all. Upwards of fifty died on the new route..."

--Mariah King, 1845

Meek was a proud man, certain of his capabilities as a guide. But as the party came down East Cow Creek into the Harney Basin, witnesses watched as his calm face "changed to one of complete bewilderment, as if he were seeing the country for the first time." Nothing looked the same as it had a decade earlier.

They were lost.

Sarah "Sally" King Chambers, along with many others, succumbed to "camp fever" on September 3rd, and was buried by her husband Rowland north of what is now Juntura.

Persisting in their journey, the train trailed southward along the banks of the Silvies River, venturing onward to the expansive lakebed, where their direction shifted westward. As they endeavored to reach Silver Creek, voices within the vanguard group clamored to maintain their westward trajectory, advocating the discovery of a pass over the formidable Cascades. Meek, however, proposed a different strategy. He sought to pursue a path northward by following the sinuous flow of Silver Creek. But his suggestion met with defiant opposition, and the starving, dehydrated people adamantly declined to adhere to his guidance.

"We camped at a spring which we gave the name of "The Lost Hollow" because there was very little water there. We had men out in every direction in search of water. They traveled 40 or 50 miles in search of water but found none. You cannot imagine how we all felt. Go back, we could not and we knew not what was before us. Our provisions were failing us. There was sorrow and dismay depicted on every countenance. We were like mariners lost at sea and in this mountainous wilderness we had to remain for five days. At last we concluded to take a Northwesterly direction....After we got in the right direction, people began to get sick...."

--Betsy Bailey in a letter to her sister, 1849

Splitting Up

At this point, the immigrants were divided on what to do. Follow the man who'd guided them into disaster, or strike out alone, following their instincts to reach civilization.

Related: A Trail Of Tears And Blood: Hiking Amanda’s Trail On The Oregon Coast

As the wagon train arrived at the springs cradling the south fork of the Crooked River, they found themselves at a crossroads. One faction pivoted westward while the other forged northward. The more populous contingent, under the leadership of Samuel Parker, trekked up to Steen's Ridge - a path so deeply etched into the landscape that even today, the ghostly echoes of their wagon ruts are visible. They were committed to tracing the serpentine path of the Crooked River.

In contrast, the smaller, less populous band, in the company of Solomon Tetherow, pressed westward. They navigated along the northern flank of Hampton Butte and then aligned their path with Bear Creek. Steven Meek, the once-revered guide, accompanied this smaller troupe in their journey. This group fared the worst. Meek assured them that the salvation of The Dalles was only two days away, but it took a relief party ten days to reach the northern settlement, arriving in such bad condition that the men were too weak to dismount their horses without aid.

On September 26, 1845, both groups arrived on the same day at Sagebrush Springs near present-day Gateway, Oregon, having all traveled miles upon miles without water.

Finding Their Bearings

Native American tribes added another layer of danger. Stories of hostile encounters filled the pioneers with dread, and while actual violent confrontations were rare, the fear of such attacks added to the psychological toll of the journey. The physical hardships were compounded by the psychological strain. The sense of betrayal, the fear of the unknown, and the loss of loved ones pushed many to their limits. Tensions ran high within the group, with accusations and blame directed at their erstwhile guide, Steven Meek.

In fact, it was Native Americans who undoubtedly saved Meek's life.

Related: Marie Dorion: The Most Badass Woman in Oregon History

An angry father who's two sons had succumbed to death on the cutoff was calling for a gang to lynch Steven Meek. The pioneers who had once placed their faith in Meek now called for his head. In the face of adversity, the legendary mountain man was reduced to a man, mere and mortal, as vulnerable as the pioneers he had pledged to protect.

Catching wind of his impending doom, Meek disappeared into the wilderness with his wife, reaching Sherars Falls on the Deschutes River where they encountered a group of local natives who swiftly orchestrated a rescue. A rope was strung across the turbulent water, providing a lifeline for Meek and his wife. With sturdy ropes securely fastened around them, they were cautiously ushered through the tumultuous water, eluding the brewing storm of retaliation.

After rushing to Wascopam Mission at The Dalles, Meek and his wife returned with relief in the form of rescuers from the Willamette Valley. The train had finally found its salvation.

The End of the Journey

In a painstaking process to aid their hazardous river crossing, the settlers were forced to meticulously disassemble their wagons. Some transformed their wagon boxes into makeshift boats. With ropes as their guiding system, they navigated the swift river current, embarked from the lower banks.

Others, however, opted for a mechanical solution, utilizing a rope and pulley system installed above the towering walls of the narrow canyon, approximately two miles, or three-point-two kilometers, downstream. This intricate process was time-consuming, stretching nearly two weeks to transport everyone in the wagon train across the perilous waters.

Pushed to their limits, both physically and emotionally, the famished and fatigued settlers finally found respite. They began arriving at The Dalles around the second week of October, 1845. It's estimated that a further 25 of the immigrants died after reaching The Dalles, succumbing to exhaustion and undernourishment.

The precise number of lives lost during the Meek Cutoff remains a topic of historical debate. Conservative estimates put the death toll around twenty-three, while some argue it was significantly higher, possibly reaching into the hundreds. The truth likely lies somewhere in between.

Meek's Cutoff: The Aftermath

In the year 1853, a fresh band of pioneers broke away from the Oregon Trail at Vale. This subsequent wave of emigration was spearheaded by Elijah Elliott. With a few deviations, Elliott retraced the trail blazed by Meek in his tumultuous 1845 journey. However, a significant divergence occurred upon reaching the Deschutes River.

Rather than following Meek's northerly turn, Elliott chose a southerly route, guiding the caravan up the Deschutes approximately 30 miles. There, a freshly cut trail awaited their wagon train - a novel route crafted specifically for their journey. This newly minted road traversed the Cascades in the vicinity of what is now known as Willamette Pass and gained recognition as the Free Emigrant Road.

The Meek Cutoff, a supposed shortcut to prosperity, instead became a 200-mile detour into despair. The exact number of lives claimed by this ill-fated journey remains unknown, but the story lives on as a stark reminder of the toll exacted by the relentless pursuit of the American Dream.

In the end, Steven Meek, the man, was dwarfed by the legendary persona he had created. Yet, his name is forever etched into the bedrock of the American West. The Meek Cutoff is not a story of destination but a tale of the journey itself. It is a saga of human grit and tenacity, a parable of trust, a ballad of disillusionment, and a testament to survival. In the harshest of conditions, the human spirit endured, leaving us with a legacy that is as enduring as the wagon wheel ruts still visible in the Oregon desert.

So let us remember the saga of Steven Meek, not as a story of failure, but as a testament to the enduring strength and audacity of the pioneers who dared to dream of a better life in the great American West. The tale of the Meek Cutoff stands as an enduring legend, a poignant testament to the indomitable spirit of adventure and the relentless pursuit of hope against all odds.