In 1843, our Oregon pioneer forefathers gathered in a series of meetings that would unite them to a common purpose while ultimately causing the extinction of the indigenous Gray Wolf from our state lands.

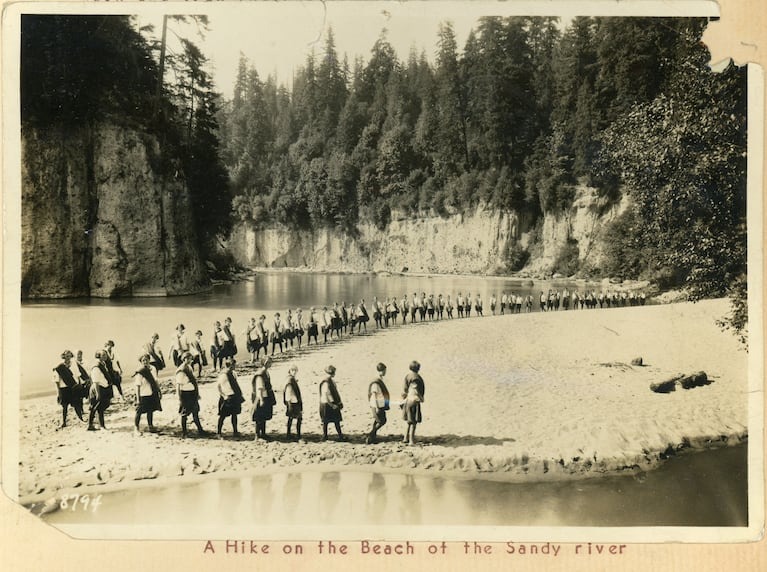

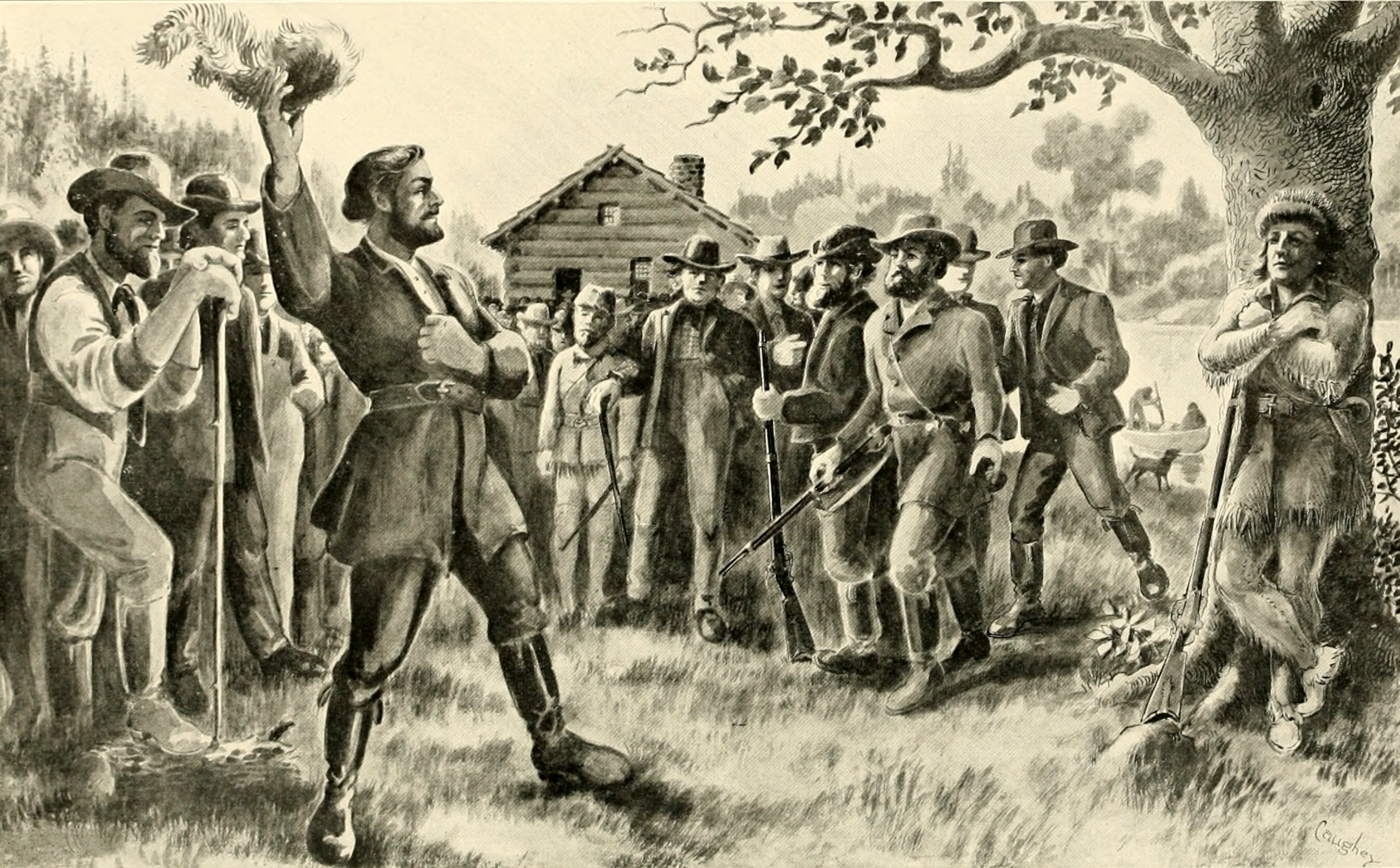

Joseph Meek leads the Champoeg or "Wolf Meetings" of 1843 / Image via Wikipedia Commons

Wolves were as troublesome to early settlers and their livestock as they are today. "Efforts to destroy the wolf in this country were instrumental in formation of the Oregon Territory," wrote Stanley P. Young and Edward A. Goldman in the 1944 book, "Wolves of North America." "The 'wolf meetings' of Oregon … drew pioneer leaders of the northwest together as did no other objective."

By 1946 the last known Gray Wolf in Oregon was slaughtered in the Umpqua National Forest.

Gray Wolf profile / Image via Envato

65 years later, OR-7 (fondly nicknamed "Journey") returned to Oregon from a 1,200-mile trek into California from his Imnaha, Oregon pack. On that trip, he crossed Interstate 84 and U.S. Routes 26, 395, 20 and 97. His mission? To mind a mate. At the age of five, "Journey" was already at the age when most Gray Wolves have reached the end of their wild lives.

OR-7 crossed the border from California to Oregon and back several times, finally mating and establishing a territory in Klamath and Jackson counties in 2013, producing three pups with his mate in 2014. This would come to be the first wolf pack in Western Oregon since the animals were exterminated in the 1940s. A pup born to OR-7 in 2014 traveled across the border and founded the Lassen Pack, California's only known wolf pack, in 2016, and had three litters of pups.

"Journey" became the subject of two films and multiple books and symbolized all the promise and peril of grey wolves reestablishing their ancestral homelands in the West.

A wolf pack in the snow / Image via Envato

Wolves are incredibly similar to humans. They’re born into families, transition through an adolescent and young adult phase, then set off to find a mate, claim territory, and eventually mature into family life. Many Native American tribes held the wolf in such high esteem, movements were patterned after them, family dynamics were adopted, respect was given with many rituals, as well as clans named after these majestic animals. In many tribes, the wolf is revered as a brother or sister, even a teacher or guide.

Wolves and Native American culture are intertwined. Image via / canstockphoto

To American settlers, wolves are less respected. OR-7's Rouge Pack has been blamed for 24 confirmed livestock depredations, including nine incidents in 2019. Nevertheless, the species remains protected in the western two-thirds of Oregon under the federal Endangered Species Act.

Oregon wildlife officials said Wednesday that it looks increasingly likely OR-7 died last winter; he hasn’t been seen with his Rogue Pack for months even while other members of the pack remain. He was estimated at 11 years old, while most wolves in the wild only live to 5 or 6.

“If he is gone, he will have left an indelible mark in the history of wolf recovery,” said Weiss, West Coast wolf advocate for the Center for Biological Diversity. “His life and story contributed significantly to human understanding of what wolves are all about.”